Two months ago, after literal years of applying to zoos* across (I counted) 26 States, I finally started a full-time, big girl job at the Alaska Zoo. And I love it here.

*I’m going to use the word Zoo a bit generally to mean: ethical non-profit institution that cares for wildlife for purposes of conservation, education, and other positive not-for-profit reasons.

I have loved zoos for as long as I can remember. The Denver Zoo was my favorite day trip and when it was my turn to pick somewhere to go in new cities on road trips and vacations I would always fight for the local zoo. This mentality has brought me to 30+ zoos in at least 15 states, 6 countries, and 3 continents. And, at least for as long as I can remember, I ran around all of these zoos with some model of digital camera, snapping progressively better photos as both technology and my skill to point and shoot improved. My laptop, and two generations of laptops before it, are filled with folders of zoo pictures. You should see my poor Desktop the last month as I navigated a few hundred pictures of bear cubs and like, at least five or six of some other species.

Animals, be it wildlife, zoo life, or house cats, remain my favorite thing to photograph. Sure, Alaskan landscapes are aggressively pretty but damn is that bear making excellent faces and they are subjects that are moving and changing. I am also endlessly fascinated by learning about all of these animals and their differences and similarities. Nature is wild and the fact that humans came out on top feels fully like sheer, dumb, evolutionary luck that we figured out how to ward off apex predators faster than they could eat us. In another life I would have been very happy studying zoology or vet sciences or specializing in very specific behaviors of very specific animals and writing long winded papers about them. I’m already great at long winded writing. Of course, this is also the alternate life where I had the time for upper-level Biology classes in high school and was also completely okay with the idea of dissecting a pig fetus at 8 a.m. and then going about the rest of my day smelling like formaldehyde and pig juices. Alas. Instead, I poured all of my free time and then some into Yearbook which turned into a journalism major which turned into communications jobs which turned into prolonged underemployment which turned into moving to Alaska which turned into right now: me, writing a blog for some reason.

Despite at least three counts of me being painfully sick at a zoo, I have never once let it taint my experiences. In fact it was after a particularly miserable experience of me nearly blacking out at the Denver Zoo that I bought myself a membership to go back repeatedly. The fact that I threw up, quite a bit, before me and my friends went in and I stood up after and said “Aight, let’s go see some lions” seemed like a good indication that I should come back a lot. For the record, the lions are as far as I got that day before I realized that being drenched in sweat while also shivering and being too weak and dizzy to walk in a straight line were all poor Zoo-going conditions so my friends ushered me back to the gate, the zoo gave me ice water and called some EMTs, and my friend drove me home. The next day I bought a membership and, despite hating the drive to Denver, used it kind of a lot.

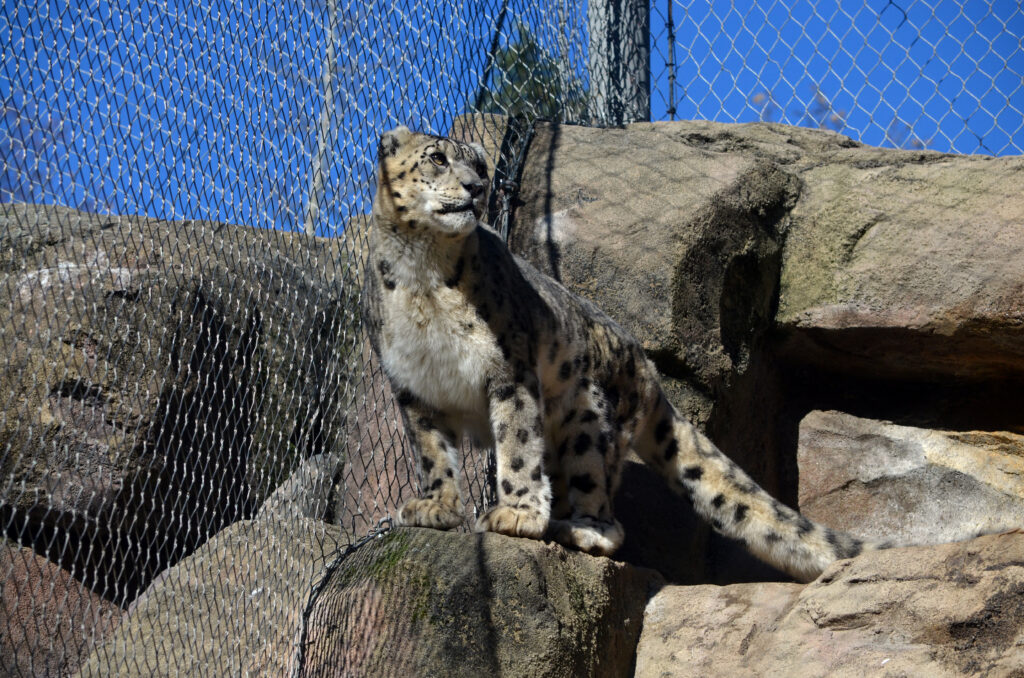

I’m either incredibly endearing or endlessly annoying at zoos because I know a lot about all of the animals and will spit out the fun facts unless you explicitly tell me to stop. At the zoos I’m familiar with, I can name (as in the animals’ individual names, not their species) a decent number of the animals and recite their recent histories because zoos are some of the few accounts I still enjoy following on social media and somehow it is the information they post that sticks around in my brain rather than where I last left my wallet or what time I was supposed to meet someone at. At the Denver Zoo in particular, I have facts for just about every large exhibit and can pretty consistently answer the common questions I overhear from other guests. Now that I work at a zoo, there’s no holding me back because I’m no longer just a nosy stranger but instead am helpful and just doing my job. Ha!

To clarify, I am not working with animals or giving tours but walking around the zoo when it’s slow is a perk of the job. For me at least, it’s the main perk (sorry, health insurance). Also, it’s November in Alaska, — my job is going to be slow until May.

There is a nagging feeling as I write this that I should address the controversy over zoos and animals in captivity in general. I’ve been on both sides of the issue because, despite loving zoos, the “animals don’t belong in cages!” mentality is A). woke and trendy and, more importantly, B). a legitimate ethical concern because there are shitty “zoos.” (Tiger King, anyone?) Also, like a lot of similarly charged hot-topic issues, there is at least some validity to both sides. But the people demanding freedom for all captive animals and taking bolt cutters to animal enclosures are fully misguided. Most animals who have spent time in captivity will not survive in the wild. And animals who are in reputable zoos are there for a reason.

Kova is a juvenile polar bear who came to the Alaska Zoo from the North Slope about a year ago. She was separated from her mother and was making herself a little too comfortable near the housing of an oil crew so was in danger of getting shot by workers or euthanized by wildlife officials. In the state of Alaska, government agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and NOAA are in charge of all wildlife relocation, rehabilitation, or rescue so Kova’s relocation was a government decision, rather than any zoos’. The Alaska Zoo is one of the best zoos in the United States to care for orphaned polar bear cubs because of past experience, habitat space, and it has the most appropriate climate. Also, of note, this photo is taken from an area locked off from the public path. For obvious reasons, guests cannot reach the polar bear (see: Binky).

People from legitimate zoos are not just flying to Africa, taking a baby lion, and pretending it’s an emotional support animal to fly it back to America as an attraction at their zoo. There are organizations and safeguards, not to mention public relations backlash, that are preventing that. But I get that unfortunately that wasn’t the case 50 or so years ago because that is the story behind a lot of zoos. So, like a lot of things in the world, it is important to take the problematic history into account. And that starts with my zoo.

The Alaska Zoo exists because a toilet paper company decided that it would be a funny joke to offer a baby elephant as a prize alternative to cold, hard cash and the winner of the competition decided to take them up on it. That elephant, Annabelle, came from a circus and almost certainly had a less than ethical origin story getting there. Fortunately, Annabelle’s story turned out well because the competition winner quickly realized he couldn’t safely keep the elephant come winter and found someone with a heated barn that could. And that person, Sammye Seawell, went on to give Annabelle the best life an orphaned elephant transplanted into Alaska could get.

From that early history, Annabelle paved a path for hundreds of orphaned, injured, or captive-bred animals to find a safe home at the Alaska Zoo. And that’s pretty incredible. I don’t personally know the history of every single animal who is at the Alaska Zoo (yet) to do a full break down of where everyone came from. But now, 50 years after Annabelle, every animal at the Alaska Zoo was either orphaned or injured in the wild, born at another reputable zoo, or rescued from a previous unethical owner. No stolen polar bears. And yes, we now know that animals that would rarely see snow in the wild shouldn’t move up to just below the Artic Circle anymore. So no freezing elephants either. Instead, it’s native Alaskan species and “Arctic, sub-Arctic and like climate species.”

Which means three species of bear, so I’m pleased.